A fusion of travel and literature where literature acts as the catalyst, transforming travel into an intimate exploration of self

“Literature is the most agreeable way of ignoring life.”

― Fernando Pessoa, The Book of Disquiet

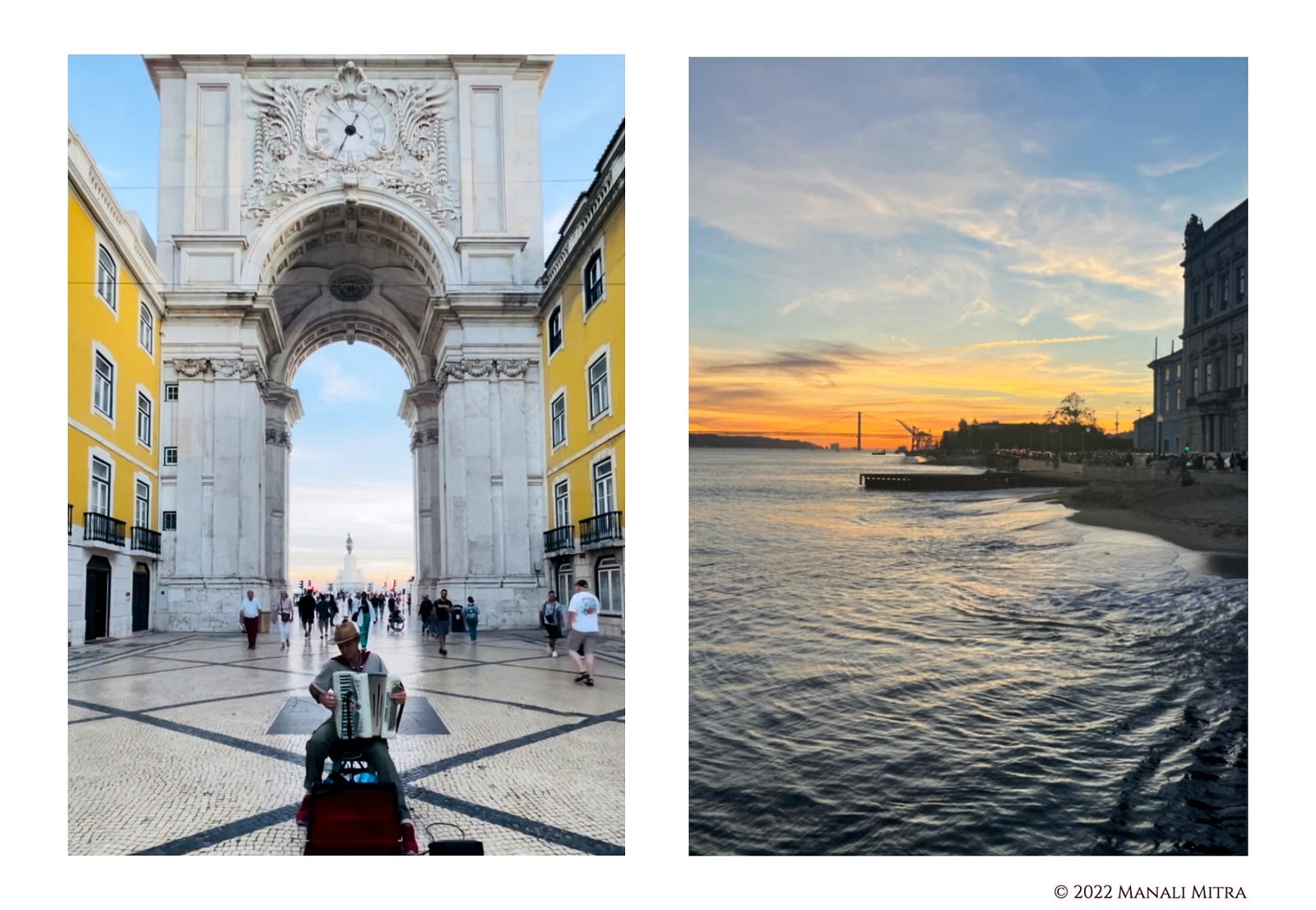

Lisbon, the city that illuminates history and culture, has been the soul city of some great writers. After years of traveling vicariously in and around Lisbon through José Saramago’s novels, I was finally there!

My first visual of Lisbon was through Saramago’s tour de force, ‘The Year of the Death of Ricardo Reis’ —

“The sea ends, and the earth begins. It is raining over the colorless city. The waters of the river are polluted with mud, the riverbanks flooded. A dark vessel, the Highland Brigade, ascends the somber river and is about to anchor at the quay of Alcântara.”

The eponymous protagonist, Ricardo Reis, one of the many heteronyms of the modernist poet Fernando Pessoa, returns to Lisbon amidst political turmoil in 1935 after 16 years of exile in Brazil. Ricardo Reis strolls around Lisbon’s boulevards and narrow streets, observing the changes that have taken place since his departure. One day, he stops by Fernando Pessoa’s graveyard. The ghost of Fernando Pessoa then starts visiting Ricardo Reis, and they frequently engage in conversations that reflect Pessoa’s philosophical musings. Throughout the book, Ricardo Reis wanders the streets of Lisbon, yielding an intriguing travelogue.

When I reached the city, the ‘rua’ and the ‘praca’ were already so familiar!

I arrived at my hotel, Palacio do Visconde. It’s on a narrow street along the №28 classic Lisbon tram line. I could see the №28 pass by from my upper-floor room and hear “the creaking on its turn, and the tinkling of its little bells.” The hotel is a recently restored ‘Palacio’ with minimal modern fittings. The Venetian paintings on the ceilings and the Victorian oak upright piano exuded an old-world charm. Maria, the receptionist, tried her best to make me comfortable by offering me a cup of coffee. I indulged. Without wasting much time, I rushed to catch the tram to Praça do Comércio.

№28 has a stop right in front of the hotel. I embarked and luckily found a seat by the window. The ticket cost 3 euros. This is the original 1930s Remodelado tram. The tram ride reminded me of one memorable passage from Saramago’s book, ‘The Year of the Death of Ricardo Reis —

“The pavement was wet, slippery, the tram lines gleamed all the way up the Rua do Alecrim to the right. Who knows what star or kite holds them at that point, where, as the textbook informs us, parallel lines meet at infinity, an infinity that must be truly vast to accommodate so many things, dimensions, lines straight and curved and intersecting, the trams that go up these tracks and the passengers inside the trams, the light in the eyes of every passenger, the echo of words, the inaudible friction of thoughts. A whistling up at a window as if giving a signal, Well then, are you coming down or not. It’s still early, a voice replies, whether of a man or a woman it does not matter, we shall encounter it again at infinity.”

The tram meandered through the narrow streets of Alfama with tight turns and twists. The familiar rumbling of the tram’s clanky old engine unlocked many happy childhood memories — with a wistful smile, I remembered my long, lazy, romantic rides in my ‘city of joy.’

Lost in my thoughts, I didn’t realize the tram was crowded by then! After crossing the Lisbon Cathedral, the tram arrived at the famous Baixa district. I made my way through to get off at the next stop. I got down and strolled to Praça do Comércio. I reached the Lisbon Story Center — some fascinating interactive exhibits depict Lisbon through the ages, including the massive earthquake of 1755.

But, I went there to see the Passarola flying machine by the Brazilian-born Portuguese priest and aviation pioneer Bartolomeu Lourenço de Gusmão. Saramago, in his other masterpiece, ‘Baltasar and Blimunda,’ sheathes magical realism and blends the lives of the two fictional young lovers with the real historical figure, Bartolomeu Gusmão, amid the Portuguese Inquisition. Baltasar, the war survivor who lost one hand, and Blimunda, who possesses a magical power of seeing into things and people, help Bartolomeu build the Passarola. They needed fuel called ‘ether’ to make it fly. ‘Ether’ is made of ‘human will’ that looks like a dark cloud. Blimunda, with her magical powers, collects the ‘wills’ in bottles, and the Passarola soar joyously toward the sky with three of them!

“Lisbon is suddenly far behind them, its outline blurred by the haze on the horizon, it is as if they had finally abandoned the port and its moorings in order to go off in pursuit of secret routes, who knows what dangers await them, what Adamastors they will encounter, what St Elmo’s fires they will see rise from the sea, what columns of water will suck in the air only to expel it once it has been salted. Then Blimunda asks, Where are we going, and the priest replies, Where the arm of Inquisition cannot reach us, if such place exists.”

Later, they abandoned the project. Priest Bartolomeu, fearing “the arm of Inquisition,” flees to Spain and later dies. Baltasar and Blimunda go to Mafra, where Baltasar works as a drover to help in the construction of the Palace-Convent of Mafra, but they make periodic visits to look after the Passarola.

From the Praça do Comércio, I started walking toward Rossio Square, a 10-minute walk.

“The heat of the sun is fierce, and the great walls of the Carmelite Convent cast their shadows over the Rossio,”

Baltasar first met Blimunda at the Rossio square, where an ‘auto-da-fé’ was taking place. Blimunda’s mother was sent into exile to Angola for having mysterious visions.

Besides the Passarola, Palace-Convent of Mafra is a central theme in ‘Baltasar and Blimunda’ — the king’s megalomania, stupidity, and vanity; the thousands of workers involved in this mammoth project — exhausted bodies, the maimed humans, the widowed families for carrying huge blocks of marble from the quarry to the site of the convent a long distance away. Baltasar and Blimunda represent the mass, the people that have been excluded and silenced by history.

“His Majesty’s labourers get to their feet, frostbitten, and weak from hunger, fortunately the henchmen have united them, since they expect to reach Mafra today”

Next day, I was all set to visit the Convent of Mafra.

I boarded the bus at Campus de Grande, which drove me to Mafra in 40 mins. Mafra is a sleepy dull town under the shade of this monster of a palace.

A Franciscan monk told King João V that if he promised God to build a Franciscan convent, God would grant him his long-desired heir! The construction of the Palace-Convent of Mafra was ordered by King João V once his wish was fulfilled. Financed by the gold and diamond mines of Brazil— Construction lasted 13 years and mobilized a vast army of workers from the entire country (a daily average of 15,000 but at the end climbing to 30,000 and a maximum of 45,000), under the command of António Ludovice, the son of the architect.In addition, 7,000 soldiers were assigned to preserve order at the construction site. They used 400 kg of gunpowder to blast through the bedrock for the laying of foundations. There was even a hospital for the sick or wounded workers. A total of 1,383 workers died during the construction.( Source- Wikipedia.)

I was astounded by the artistry of this place, and at the same time, it was heart-wrenching to think of ‘the Baltasars’ behind it. I was immersed in the tranquility of the magnificent library, built in Rococo style, that houses over 36,000 leather-bound books. Interestingly, this library is preserved by a colony of bats as they prey on insects and help protect the books! One should visit this palace to see the grandeur and cognize the grind that has gone into building this opulent edifice. Wandering from room to room, I could relate to Saramago’s sensibility.

“Your Royal Highness should be warned that the princely sum of two hundred thousand cruzados has been spent on the inauguration of the convent of Mafra and the King replied, Put in on the account, for the work is still in its initial stages, one day we shall need to total up our expenses, and we shall never know how much we have spent on the project unless we keep invoices, statements, receipts, and bulletins registering imports, we need not mention any deaths or fatalities for they come cheap.”

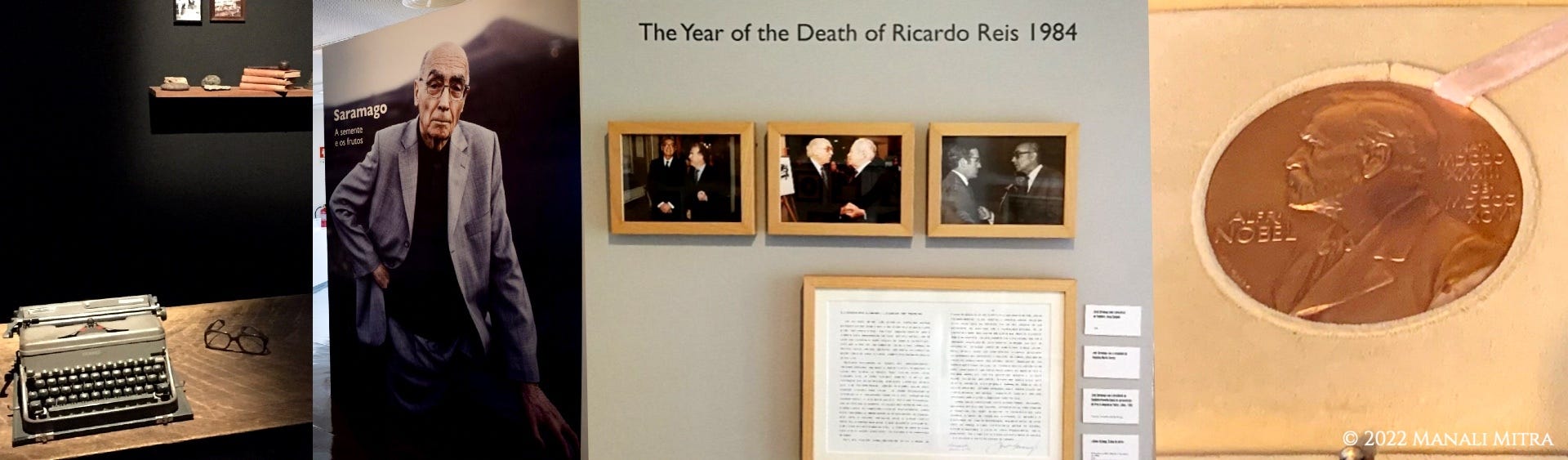

Back in Lisbon, I walked to the Casa dos Bicos, one of the few buildings that survived the disastrous 1755 earthquake. It has a quirky facade of spikes inspired by Renaissance architecture and stands right by the Tagus River. The upper floors are dedicated to the José Saramago Foundation, and the ground floor is an archaeological site exhibiting medieval Roman ruins.

The Saramago museum covers essential moments in the Nobel laureate’s life and works. Though the museum has limited English translations, I loved going through the old photographs. The omniscient narrator was raised in poverty, moved to Lisbon, lived for years under the despotic regime, and finally survived to experience post-Salazar Portugal. Each phase of his life is beautifully displayed. I was always fascinated by Saramago’s punctuation style; he said, “Punctuation was like traffic signs; too much of it distracted you from the road on which you traveled.” I was thrilled to see the Hermes typewriter on which he wrote many novels, memorabilia, and his Nobel Prize medal! After this uplifting experience, I walked out of the museum. An olive tree from Saramago’s native village, Azinhaga, is replanted right in front of the building. Supposedly, the author’s ashes are scattered under the tree. I stood there for some time, thankful to have been able to travel so far and experience this unforgettable journey.

But the journey never ends. Saramago writes in his book, ‘Journey to Portugal: In Pursuit of Portugal’s History and Culture — “The journey is never over. Only travellers come to an end. But even then they can prolong their voyage in their memories, in recollections, in stories. When the traveller sat in the sand and declared: “There’s nothing more to see” he knew it wasn’t true. The end of one journey is simply the start of another. You have to see what you’ve missed the first time, see again what you already saw, see in the springtime what you saw in the summer, in daylight what you saw at night, see the sun shining where you saw the rain falling, see the crops growing, the fruits ripen, the stone which has moved, the shadow that was not there before. You have to go back to the footsteps already taken, to go over again or add fresh ones alongside them. You have to start the journey anew. Always. The traveller sets out once more.”

© 2025 Manali Mitra. All Rights Reserved.

Leave a comment