An enriching experience at the H’ART Museum

“Color directly influences the soul. Color is the keyboard, the eyes are the hammers, the soul is the piano with many strings. The artist is the hand that plays, touching one key or another purposively, to cause vibrations in the soul.” ― Wassily Kandinsky, Concerning the Spiritual in Art.

That evening, I picked up rosé on the go and hopped onto a canal cruise. The guide’s voice crackled in those plastic earphones while the boat drifted through the Amstel River in front of the H’ART museum. And I heard the magic words: The Kandinsky exhibition! I almost spilled my wine. Years of encountering Kandinsky piecemeal, the glimpses of his works scattered worldwide had been just preludes. But here lay the magnum opus, a feast of his oeuvre under one roof!

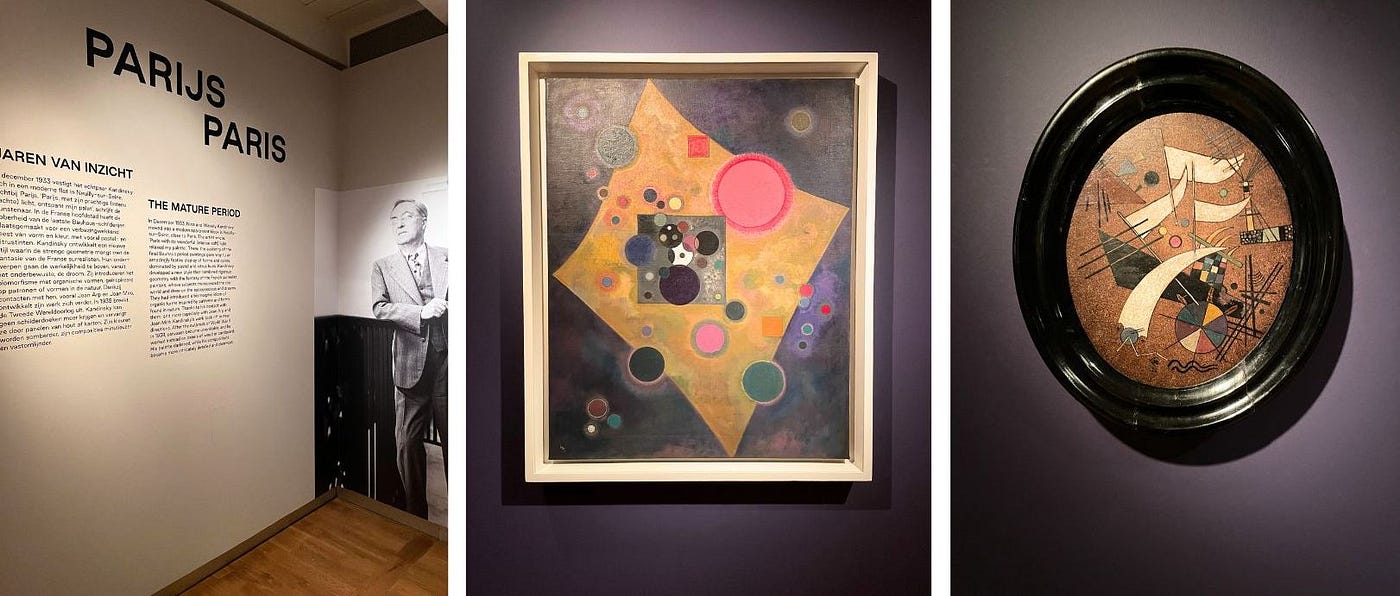

The following day, I arrived at H’ART sharp at 10 am. The exhibition was a unique collaboration between the H’ART Museum and the Centre Pompidou, the home of this incredible collection. Before entering the hall to witness over 60 masterpieces, a video installation at the entrance caught my eye. Created by artist Bink van Vollenhoven, the film featured an actor channeling Kandinsky’s voice — a beautiful prologue to the genius waiting beyond.

Kandinsky was born in Moscow in 1866 and spent his early years in Odessa. Later, he returned to Moscow for college to study law, ethnography, and economics. While in Siberia, researching peasant law amidst the pagan Zyrian tribe, he came across folk art that fascinated him. One day, he saw Monet’s “haystack” in Moscow and stared at it for several minutes before deciphering its meaning. Soon after, he went to a performance of Wagner’s Lohengrin at the Bolshoi Theatre and had a wild experience where he saw the music as colors and shapes. This might have been triggered by a rare neurological condition called synesthesia (though never proven.)

“The violins, the deep tones of the basses, and especially the wind instruments at that time embodied for me all the power of that pre- nocturnal hour. I saw all my colors in my mind; they stood before my eyes. Wild, almost crazy lines were sketched in front of me.” — Kandinsky later recollected in his 1911 book, Concerning the Spiritual in Art

After earning his PhD, Kandinsky left academia to follow his heart into the world of art. In 1896, he left Russia for Munich, a city alive with the energy of the Jugendstil (Art Nouveau) movement. Here, he learned techniques like tempera painting and wood engraving.

By 1901, Kandinsky founded the Phalanx group and an art school that welcomed women — a bold move against the rigid traditions of the Munich Academy. At this school, he met Gabriele Münter, a young painter and photographer who became his partner for the next 15 years. When the school closed in 1904, the pair decided to explore the world together, traveling through Holland, Tunisia, Italy, and Paris from 1903 until 1909. During this time, Kandinsky was inspired by landscapes, and his work exhibited rich Impressionist influences.

As I entered the hall, I was first drawn to Kandinsky’s early landscapes from 1902, which reflected his connection to nature and his evolving use of color and texture. Kochel, Alte Kesselbergstrasse captured a scenic Bavarian road rendered with bold, expressive brushstrokes. Lake and Herzogstand portrayed the interaction between the lake and the mountain. Lake and Pier I depicted a simple pier and its reflections, evoking tranquility. Am Ufer (On the Shore)brought the shoreline to life with vibrant hues and meticulous detail. These works reflected Kandinsky’s Impressionist influences in his early years.

Old Town 11 was another one of Kandinsky’s works. He painted it during a trip to Rothenburg, a medieval town in northern Bavaria, about 230 kilometers from Munich. He first visited in 1901 and returned in 1903 with Gabriele Münter. In The Steps, his autobiographical novel, he mentioned that only one painting from the trip remained.

Between May 23 and June 21, 1904, Kandinsky and Münter traveled through several Dutch towns, including Rotterdam, The Hague, Haarlem, Amsterdam, Zaandam, Edam, Volendam, Marken, Broek in Waterland, Hoorn, and Arnhem. During this journey, Kandinsky continued his experiments with polychrome compositions, working with tempera or gouache on a black background. Simultaneously, he produced numerous oil paintings in a post-impressionist style, frequently applying paint with a palette knife to create texture and depth.

One of the standout pieces from this period is the enchanting gouache Saturday Evening (Holland). The painting captures a lively Dutch waterfront, where men and women in resplendent traditional attire prepare for a Saturday night out. It is the pointillist technique of the neo-impressionists, but Kandinsky takes a unique approach — each dot of color is given its own vibrancy and presence, standing out boldly against the dark background.

Another series done during this time that gripped me was his Venice series. Painted in tempera on cardboard—a style that I wouldn’t often associate with Kandinsky—this was not the Venice of Turner’s watercolors or Canaletto’s cityscapes. It was something else entirely—Venice at night. The canals seemed to swirl with movement.

In the summer of 1908, Kandinsky and Münter returned to Munich but soon moved toward the rural town of Murnau am Staffelsee, mesmerized by its traditional folk art and picturesque surroundings. Their time there was transformative for Kandinsky’s style — brushstrokes became bolder and vibrant, breaking free from the constraints of realism.

Kandinsky categorized his paintings into three groups: Impressions, which captured direct observations of nature; Improvisations, which were more unconscious expressions of inner emotions; and Compositions, which were carefully refined and worked on over time. As he explained in Concerning the Spiritual in Art, Improvisations were sudden, instinctive responses to internal experiences, while Compositions evolved more deliberately.

For Kandinsky, Improvisations were essential for revealing the emotional “sound” of visual experience. Between 1909 and the start of World War I, he painted over 30 of them.

In 1909, Kandinsky painted Studie zu Improvisation 3, one of the early pieces from his Improvisations series. In this masterpiece, a rider on horseback charges across a white bridge toward a bright yellow fortress, surrounded by a vibrant, dreamlike landscape. This scene, painted in Kandinsky’s signature expressive style, reflects both medieval themes and the striking colors of Tunisia, which he had visited in 1904–05. Many of his Improvisations from this period were inspired by the intense light and vivid hues he witnessed there.

The “rider” motif was significant to Kandinsky. It first appeared in his 1903 famous painting Der Blaue Reiter and later became the name of the artistic movement he founded with Franz Marc in 1911. For Kandinsky, the rider often symbolized Saint George, the patron saint of Moscow, known for slaying the dragon. This battle, in the artist’s view, represented the struggle of the human spirit against materialism.

By December 1911, Kandinsky formalized his ideas on abstraction in his book Concerning the Spiritual in Art — “Color harmony can rest only on the principle of the corresponding vibration of the human soul. This basis can be considered as the principle of innermost necessity.”

He and Franz Marc published the Blaue Reiter Almanach (Blue Rider Almanac), a groundbreaking manifesto on the synthesis of artistic disciplines freed from all boundaries. They saw abstract forms and bright colors as having spiritual meaning, helping to oppose the materialism and corruption at that time.

“Music is the ultimate teacher.” ― Wassily Kandinsky

The same year, he painted Picture with a Black Arch — Three blocks of color form a triangle, held by a bold black line resembling a douga—the curved wooden arch used to harness horses to a Russian troika. The presence of black lines going in every direction amplifies the principle of dissonance that Kandinsky discovered in the musical composition of Arnold Schönberg. He wrote in his letter to Schönberg, “I believe that nowadays we cannot find our harmony in ‘geometric’ nature, but rather in the most anti-geometric, illogical way possible. And this path is that of ‘dissonance within art’ — in painting as well as in music. And ‘today’s’ pictorial and musical dissonance is nothing more than ‘tomorrow’s’ consonance.”

Kandinsky believed that the painter had to work in the same way as a composer. Instead of notes, they use color and shapes to create compositions that vibrate with the viewer’s very soul. The principle of dissonance became a defining element of his work between 1908 and 1914.

I came across a very interesting video worth sharing, showing a piece of art being created.

Another brilliant artwork on display was Painting with Red Spot, 1914. It represents the peak of Kandinsky’s abstract explorations in Munich. It abandons recognizable forms, instead using flowing colors to create movement and contrast. The only distinct shape is a red spot on the upper left, which gives the work its title.

On August 1, 1914, as Germany declared war on Russia, Kandinsky was forced to leave what had suddenly become enemy territory. In a state of emotional upheaval, he returned to his homeland, but the turbulent times impacted his work — he didn’t produce a single oil painting in 1915. Instead, he focused entirely on abstract graphic pieces, many of which reflected the starkness of the period.

In 1917, during a summer holiday with his new wife, Nina Andreevskaya, he briefly revisited his earlier figurative style in a portrait of her. However, after the October Revolution, his role shifted from artist to cultural reformer. He became actively involved in reshaping Russia’s art institutions under the new Soviet regime.

Produced during Kandinsky’s Moscow period, In Grey is considered an important piece of work. German art critic Will Grohmann described it as both intricate and unsettling in its energy, viewing it as part of the artist’s ongoing exploration. The painting is notable for its subdued tones, punctuated by bursts of primary colors, and for its floating forms that seem to drift in an endless space. In the top left corner, a shape resembling a star is again a douga — a wooden arch used to harness horses to a troika. Reflecting on the piece in 1936, Kandinsky wrote, “In Grey marked the end of my dramatic period.”

Later, he moved toward a more structured approach, where clear geometric forms took center stage within a unified composition. Kandinsky’s work aligned more closely with the geometric precision of Suprematism and Constructivism, echoing the avant-garde movement that was sweeping through Russia.

In 1920, Kandinsky became a professor at the University of Moscow and was honored with a state-organized solo exhibition. The following year, he established the Russian Academy of Artistic Sciences. However, as the Soviet government shifted its focus from avant-garde art to social realism, he and his wife decided to leave Moscow for Berlin by the end of 1921 to start afresh.

In 1921, Walter Gropius, the director of the Bauhaus school in Weimar, invited Kandinsky to join its faculty. Founded in 1919, the Bauhaus embraced a multidisciplinary and holistic approach to the arts, making it ideal for Kandinsky’s evolving vision. He arrived in Berlin just before Christmas, physically drained and malnourished after enduring the hardships of post-revolutionary Russia. It took several months for him to regain his strength, but by 1922, he was officially appointed as a teacher.

As head of the mural painting workshop at the Bauhaus, Kandinsky created some of his most significant works. In 1922, Walter Gropius assigned him the design of an entrance hall for a contemporary art museum, which was later showcased at the Juryfreie exhibition in Berlin.

Collaborating with his students, Kandinsky painted large-scale canvases where fluid lines and vivid colors orchestrated a striking composition against black and brown ochre background. The simplified motifs foreshadowed the geometric approach that would define his Bauhaus period. While the original decor no longer survives, Nina Kandinsky later donated the maquettes — gouache on black and brown ochre backgrounds to the Musée National d’Art Moderne, which provided the foundation for a reconstruction. It was unveiled with the opening of the Centre Pompidou in 1977. Interestingly, Kandinsky later described the works of the Weimar years as his ‘cold period.’

Kandinsky’s Auf Weiss II, which once hung in his dining room in Dessau, is one of the most important works of his Bauhaus period. It revisits the theme of intersecting diagonals from a 1920 painting while reflecting on his earlier works from the 1910s, where colors and lines collided like forces in motion. The nearly square white background, which gives the painting its name, resonates with the suprematism of Kazimir Malevich, whose work Kandinsky discovered in Russia. This dynamic interplay of elements recalls the motif of St. George carrying a lance — a subject Kandinsky had painted multiple times.

Between 1925 and 1928, while living in Dessau, Kandinsky became so captivated by the circle that his wife, Nina, called it his “circle era.” In his biography of the artist, art critic Will Grohmann shares an interesting remark from Kandinsky: that the reason for his frequent and passionate use of the circle in recent years had nothing to do with its geometrical shape or geometrical properties but instead with his own profound feeling about the internal power of the form and its innumerable variations.

To create Accent in Pink, Kandinsky used the new Bauhaus airbrushing technique. The painting shows the tremendous chromatic subtlety achieved by the artist at this time. Its delicate chiaroscuro effects give the surface an almost cosmic dimension. Kandinsky gave this painting to Nina for her birthday on January 27, 1930.

During this time at Bauhaus, Kandinsky collaborated with artists such as Paul Klee, Marianne Brandt, Oskar Schlemmer, and Marcel Breuer. In 1926, he published his second major theoretical work, Point and Line to Plane. Between 1925, when the Bauhaus relocated to Dessau, and 1933, when Hitler’s rise to power led to the school’s closure, Kandinsky created an impressive 289 watercolors and 259 oil paintings. Once again, he was forced into exile , finding refuge in Paris.

Paris turned out to be an intensely creative period for Kandinsky. Free from teaching and administrative duties, he devoted himself entirely to painting. Moving beyond the rigid geometry of the Bauhaus, Kandinsky embraced softer, more dynamic forms, often inspired by biology — his work now had shapes resembling embryos, larvae, and microscopic organisms. His interest in natural sciences, particularly embryology, zoology, and botany, was reflected in his art, and he collected scientific illustrations and books on these subjects.

In December 1933, Kandinsky and his wife Nina settled in Neuilly-sur-Seine, near Paris. The city’s soft yet vibrant light profoundly affected his color palette, shifting it from the austere tones of his Bauhaus years to bright pastel and citrus hues. While Cubism and Surrealism dominated the Parisian art scene, he remained steadfast in his commitment to abstraction, defending its importance in art journals. His work evolved further through his interactions with surrealist artists like Jean Arp and Joan Miró, who blended precise geometry with organic, dreamlike forms.

However, with the outbreak of World War II in 1939, art supplies became scarce, forcing him to paint on wood or cardboard instead of canvas. His color palette darkened, and his compositions became more intricate, reflecting the turbulent times.

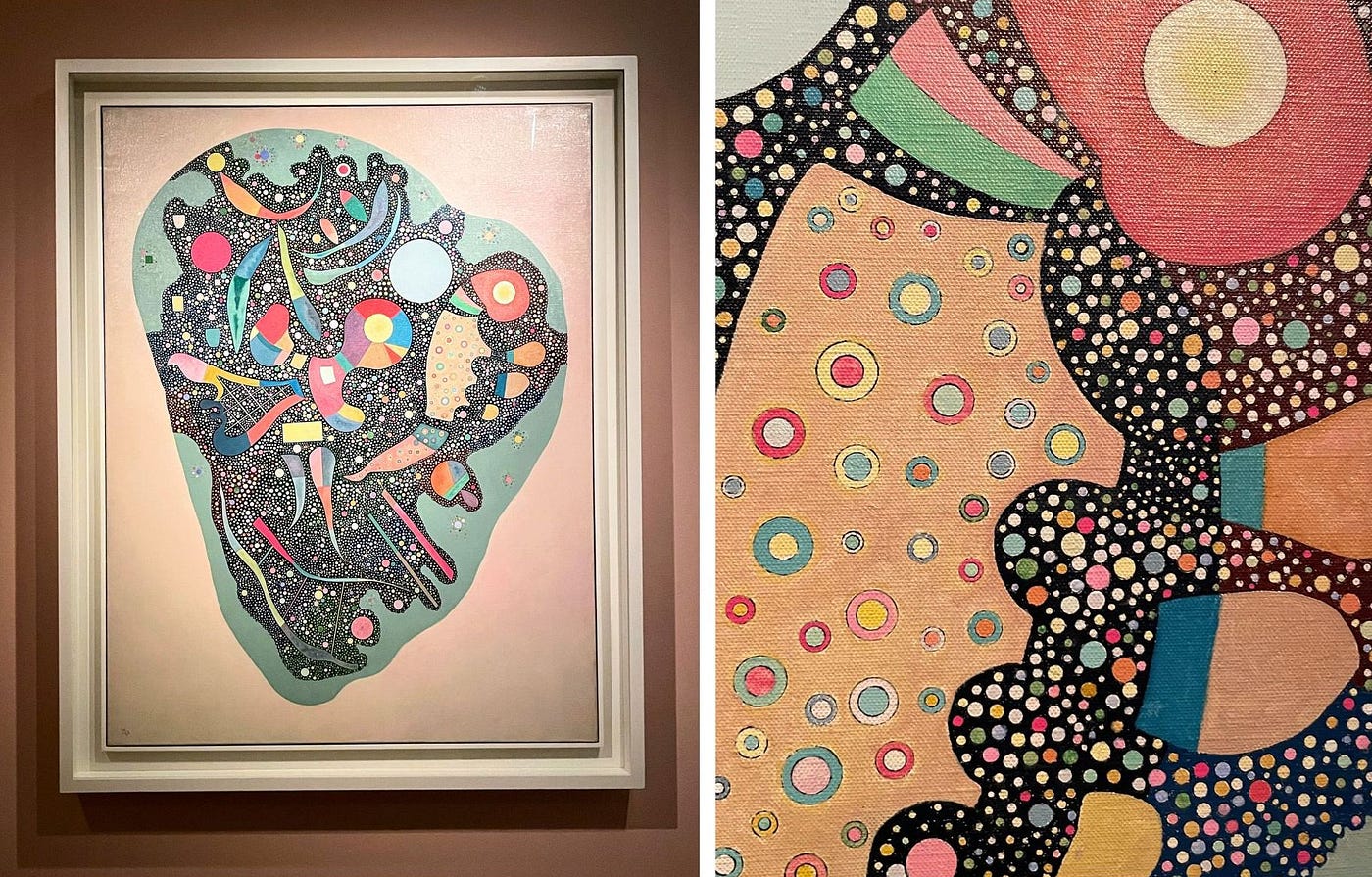

Kandinsky created Colourful Ensemble in 1938 as an Easter gift for his wife, Nina. He drew inspiration from the intricately painted eggs exchanged in Russia at the end of Lent and the opulent Fabergé eggs adorned with precious stones and enamel, gifted by the Tsars to their wives. The composition reflects the structure of a nesting doll, where each layer seamlessly fits within the next — from the broad expanse of the canvas to the tiniest detail of a single dot. Its original French title, Entassement réglé (meaning “ordered heap”), reflects Kandinsky’s exploration of harmony and contrast, balancing order with chaos and unity with multiplicity. The dense clustering of dots forms a grid that is a foundation for floating shapes reminiscent of microscopic organisms, interwoven with recognizable symbols like a ladder, an animal, and a gusli, a traditional Russian lyre-like instrument.

Another 1939 painting that unexpectedly echoed his earlier style is Simple Complexity — an intriguing mix of past and present that captured his Bauhaus precision and Parisian fluidity. An Intimate Party (1942) reflects Kandinsky’s deep dive into a vibrant microcosm, an artistic refuge from the anxieties of war.

There were a few unfinished works on display. Accord Réciproque, painted in early 1942, was the final completed one. With its cool tones and the glossy sheen of Ripolin, this final large-scale canvas was Kandinsky’s farewell to his Parisian years. With a balanced geometric abstraction and organic fluidity, the work is a beautiful culmination of his artistic journey.

After his passing, his wife, Nina, chose this painting to be placed behind him as he lay in an open casket in his studio—an intimate tribute in keeping with Russian tradition.

Kandinsky painted through wars, upheavals, and exile, yet his art never surrendered to darkness. After four wholesome hours in the museum, I felt I had known him in person. Standing in front of the last work of this exhibit was like reading the last page of a novel that one doesn’t want to end.

I left the exhibition grateful, moved, and carrying a piece of Wassily Kandinsky’s world.

“Everything that is dead quivers. Not only the things of poetry, stars, moon, wood, flowers, but even a white trouser button glittering out of a puddle in the street… Everything has a secret soul, which is silent more often than it speaks.” ― Wassily Kandinsky

References:

Wall Texts & Exhibition Descriptions:

The Kandinsky Exhibition at H’ART Museum, Amsterdam, 2024.

Book Reference:

Concerning the Spiritual in Art- Wassily Kandinsky.

© 2025 Manali Mitra. All Rights Reserved.

Leave a comment